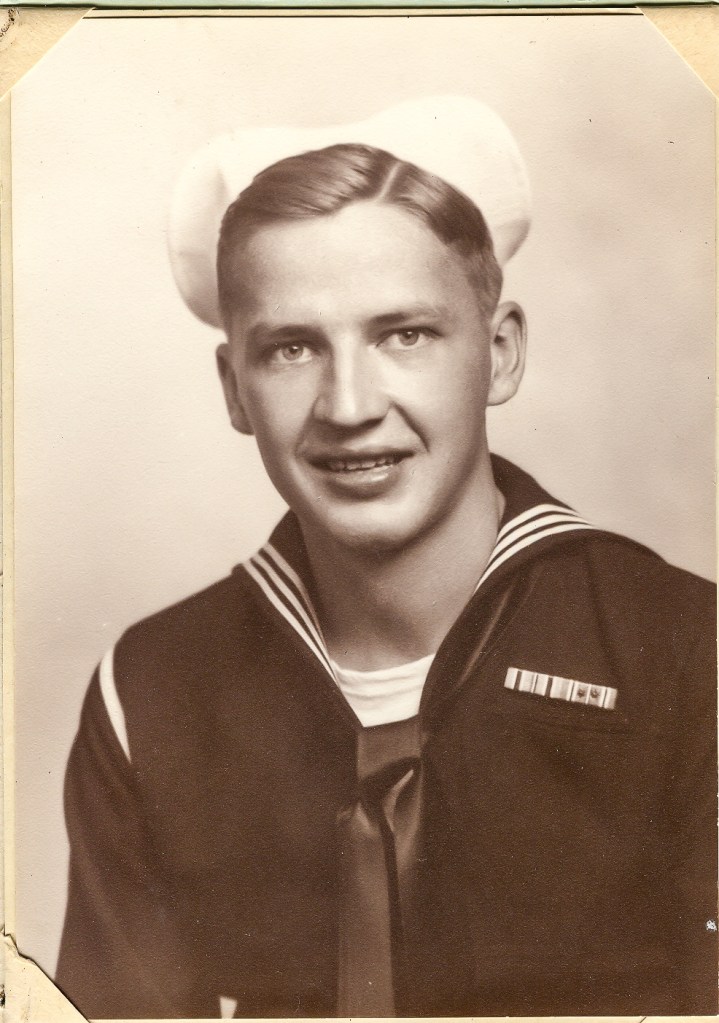

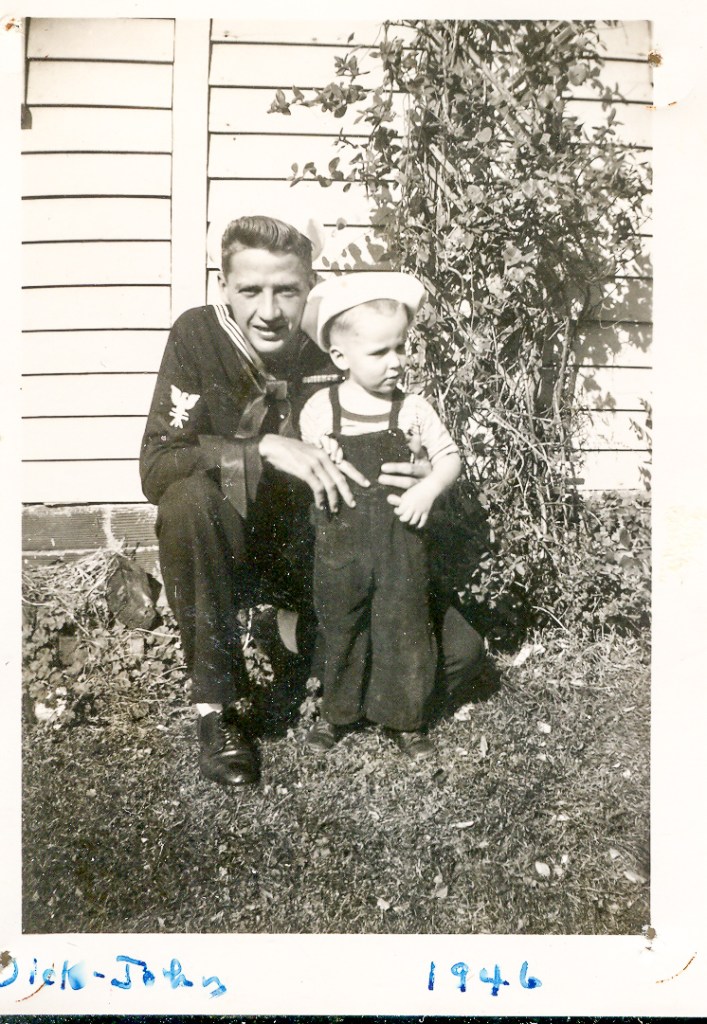

With Veteran’s Day coming up and with the passing of my 94-year old dad, Richard (Dick) Pestotnik, this week (10/30/2019), we thought it only appropriate to share his written account of his WWII experience. This writing is from many years ago. He typed it all by hand and I later scanned the typed pages to create an electronic version. His story fits nicely into the theme of our blog, remember it’s an adventure. This was his great adventure, seeing the world and the war as an 18-year old from Boone, Iowa. – John

My first memory of the war (WWII, the big one) was the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany in August of 1939. We were on a fishing trip in Minnesota and I was 14. Although the adults were somewhat depressed about what was happening I had spent years reading about the flying aces of WWI in the dime pulps and was really quite enthused about the whole thing. Besides, it would only involve Europe. If it lasted long enough I could go to Canada and join the RCAF. Going to Canada would have far different ramifications in a later war.

When France was later defeated and the Germans were pounding England even I became somewhat more realistic about the grim possibilities of the eventual outcome even though we were not yet officially involved. Initiation of the peacetime draft made our eventual involvement a distinct probability.

On December 7, 1941 I was lying on the dining room floor in front of our superheterodyne, multi-band, console Airline radio listening to a pro-football game (probably involving the Bears) when the announcer broke in to say that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor. The Japanese situation had been heating up for several months but I don’t think that anyone really expected them to attack the mighty U.S.A. Roosevelt was later to refer to December 7 as “a date that will live forever in infamy”. I was 16 and still thought that war was probably the ultimate in competitive endeavors.

Chuck (Dick’s older brother)left for the army in 1942. (Chuck had his own adventures in North Africa and Europe as a Ranger during the war. He returned home to Boone after the war, but later went back to Europe to trace the Pestotnik family roots in Yugoslavia (now Slovenia) and find a family he stayed with in France. – John)

Chuck had been away at college for several years by that time so I was used to his absence. I worked as a part time janitor at White’s Dress Shop after school and had my first taste of the hardships of war when they started paying thirty cents of my weekly three dollars in defense stamps (when you got $18.75 you could trade the book in for a bond which would be worth a cool twenty five bucks in only ten years).

Gasoline was rationed (an A sticker got you 4 gallons per week) as were tires and some food items. Scrap metal drives were big. An ordnance plant sprung up at Ankeny for the manufacture of .30 and .50 cal. ammunition. War movies wherein the treacherous Japanese gradually replaced most of the Germans as the heavies were the bulk of our entertainment. Articles (with illustrations) actually appeared in the papers pointing out the many physical differences between the Chinese (our friends) and the hated Japanese so that if you happened to encounter one on the streets of Boone you would know how to act. My own personal belief was that if his name rhymed with wong he was probably Chinese.

School was a drag when there was something as exciting as a war going on. Troop trains went through and were met by local patriotic organizations bearing food. Ames became swamped with sailors who, when Ames had become saturated, turned their attentions to the girls of Boone. It was sometime in that period that I was touched by reality when Mutt Phillips (our neighbor to the west) was reported to have been killed. He was a bombardier or navigator and I’m not sure whether it was in action or in training.

Mom and Dad refused to sign a release so that I could enlist at seventeen (thank heavens) so I waited until after my eighteenth birthday and volunteered for the draft. In June of ’43 my call came and it was off to Camp Dodge. Here I was rudely informed that I was to be a sailor rather than a Marine or Dogface. I was later to realize that this was just one of many examples of an intelligence far greater than mine that would influence my life immeasurably by steering me onto the proper path, whenever an important decision had to be made concerning career or life, regardless of how I thought I felt about it at the time. Either this or I was undoubtedly, one of the world’s luckier people.

Boot camp (Farragut, Idaho) was a mishmash of drill with dummy rifles, running the obstacle course, getting haircuts, standing guard duty (2 hr. shifts) in the furnace room and trying to look “salty”. The ability to swim was a requisite for graduation and “Clancy” Blosser, although he was an excellent high school athlete, had never learned. I had forgotten the eventual outcome until recently, when I encountered Clancy and asked him if I had taken the swimming test for him. He told me that he had taken it himself with all of the Booneites on the sideline cheering him on. Bob Doerr, Bob Mickel, Bud Todd, Bob Grabau, Clancy and I had gone to Boot camp together. Anyway, Clancy said that he had started at surface level and had finished, twenty five yards later, at a depth of around eight feet. Knowing that burning oil on the surface formed a deadly hazard at sea we figured that Clancy had a great advantage over those of us who could only flounder along on the surface. I was later, in Ulithi, forced to swim about twenty five yards in rough but oil-free seas when our whaleboat was crunched by an LCVP during a sudden squall. Aside from total exhaustion and the extreme disappointment of failing to see my entire life flash before my eyes I survived and proved that the Navy had shown amazing foresight in the selection of survival training distances.

After boot camp, I found that I had been selected for electrician’s school and that one such school was located at Ames. Having been gone for a grand total of seven weeks I was ready for a triumphant return to the mid-west. Such was, however, not to be. I moved about a half mile down the road to Camp Scott where I was to spend the next sixteen weeks learning all there was to know about “in all cases of electro-magnetic induction the direction of the induced current flow is such that it tends to oppose the motion which produces it”. It is with extreme sadness that I must report that, not once, in subsequent life, was the need for Ohm’s (I think) law ever to surface.

A few kind words about Farragut – It was located in the mountainous Northern part of Idaho somewhere between Couer D’ Alene, Idaho and Spokane, Washington. It was a beautiful place of rugged mountains, pine trees and sparkling crisp air. Lake Pend 0′ Reille provided a large body of water where we could flounder about in our whaleboats with the long (ten feet or so) oars without oarlocks. This lake was, reportedly, over a thousand feet deep in spots. Clancy would probably have been able to make at least seventy five yards before going aground.

Home for a short leave and then off to Shoemaker, Calif. (near San Francisco) for overseas assignment. After a week or so of coming closer than ever (before or since) to freezing to death in the damp, windy Northern California climate, I was pleased to find my name in a draft for the sunny, blessedly warm, South Pacific. Four awe-inspiring days on the U. S. S. Lexington and I was dumped on the beach at Aiea naval station in Oahu, Hawaii. There is nothing quite like an aircraft carrier to impress a mid-westerner (who had been awed by the size of the whaleboats on Pend 0’Reille) with the size and complexity of a modern ship of war.

A couple of weeks of leisurely waiting (with a liberty or two in Honolulu where there was a six p.m. curfew) and I found myself on the Battleship U. S. S. Indiana for further transportation to the war. Where the Lex had impressed me with sheer size and complexity the battleship appeared to be, although extremely large, somewhat squat, completely covered with a variety of guns and totally impregnable. This impression was confirmed when I reached my eventual assigned duty station, the U. S. S. South Dakota. She had three triple mounts of sixteen inch rifles, eight dual mounts of five inch dual purpose guns, seventeen quad mounts of 40 mm. heavy machine guns and over a hundred 20 mms. She also had twin catapults with OS2U observation planes which could make catapult launched take-offs and could land in the water off the stern (in rough weather we could sweep a relatively smooth spot by turning) and be picked up by a crane mounted on the fantail.

War at sea involved being on watch approximately a third of the time, standing evening and dawn alerts at battle stations (these were, reportedly, the times of greatest hazard), and spending the remainder of the daylight hours at one’s work station. Being by this time a fire controlman rather than an electrician I stood watches in the plotting room (gunnery control) part of the time and in the sky directors (target location and tracking) for the remainder. My battle stations were also at one or the other of these locations. My work station was at the optical shop where I spent my time repairing Mk. 14 gun sights.

A little bit about fire control. The five inch section, with which I was the most familiar, was basically designed for anti-aircraft defense but was equally capable of tracking and firing at surface craft and could, by using flare or “star” projectiles, be used to illuminate surface targets for the main battery. Gunnery at sea represents a complex control problem. You are firing from a platform that is moving at 20 or so miles per hour while rolling (sideways), pitching (fore and aft) and turning. The target is likewise performing all of these maneuvers at speeds of up to three hundred or so miles per hour and, in addition, has the option of movement in the vertical plane. The sky director is manned by a control officer, a pointer (vertical movement), a trainer (horizontal movement) a radar operator (invariably referred to as a radar girl) and a range finder operator. At times there was also a phone talker although most of us wore a headset during action.

We would be directed toward a target by people in the Combat Information Center or, occasionally, by lookouts. Once we got on a target the information on elevation, bearing and range would go automatically from the director into the computer in the plotting room. The computer, by reading the changes in transmitted values, would calculate target heading, speed and attitude (diving or climbing). Once the computer indicated a probable solution to the problem the output would drive the director so that if the solution were valid the people in the director could simply ride along. Ordinarily, though, they would be making minor corrections to fine tune the computer solution. The computer would, at the same time, be generating a different set of outputs for the gun mounts under control. These would include the calculated lead angles (horizontal and vertical), fuse settings (automatically adjusted in the projectile hoists and projected to correct for the time it took to remove the projectile from the hoist, load it into the breech, load the powder and fire). The roll and pitch aspect of the problem were actually governed by a gimbal mounted gyroscope which operated in conjunction with the computer and was referred to as the “Stable Element”. Powder temperature and type (smokeless or flashless) were used to determine the initial projectile velocity (app. 2550 ft/sec.) which was entered as a variable. Range of the five inch guns was around nine miles which (coincidentally) was about the range at which the 20mm battery would commence firing (optimistic actual range 2,000yards). If my memory is correct a good five-inch gun crew could fire around twenty rounds per minute. Main battery fire control was similar but slightly more refined and with a range exceeding twenty miles.

The Mk. 14 gunsight would probably, in today’s world, be equated with the six hundred dollar toilet seat or the twelve hundred dollar crescent wrench. They consisted of an electrically projected aperture on a movable reflective, transparent surface through which the target was sighted and tracked. The attitude of the reflective surface was controlled by two air-driven gyros and lagged the movement of the gun. This put the barrel of the gun somewhat ahead of the point of aim in the direction of motion (or, led the target). Range, in increments of 400 yards, was scaled on the side of the gunsight up to 2000yards with a selector handle for manual adjustment. The twenty millimeter made a helluva racket (around 480 rounds per minute) and was terrific fun to fire but I really doubt if their use tended to shorten the war appreciably. They periodically scared the hell out of us in the sky director by firing into our radar reflector (about six feet over our heads) from a range of about twenty feet.

Army references to KP indicated that it was short term punishment for any sort of infraction. The Navy viewed it a little differently (I think) in that everyone got a three month shot of it as one of their initial shipboard experiences. You moved all of your worldly possessions to the galley where you spent several weeks learning to get into a hammock suspended about seven feet over a 6″ steel deck. Once you had mastered this little feat you could spend the next few weeks building your faith to the point at which you dared entertain the notion of actually going to sleep in this precarious position. Actually it wasn’t really all that difficult and sleeping in a hammock was a most pleasant experience. Mess-cooking (as it was called) was actually a kind of a fun thing and I think that everyone gained at least twenty pounds. Moving back to your own division was actually a bit of a downer.

Mid-Pacific liberty was not exactly like that experienced in downtown Chicago. Two bottles of beer per man along with an apple, a six pound can of spam and a couple of loaves of bread for the Division and you were ready to go over the side into a crowded LCVP for the run to the beach. I understand that Mog-Mog was originally a sand spit but by the time I got there at least the top six inches was brown, broken glass. This made it hard on the fighters (particularly those suffering knockdowns) but, after the two beers nobody particularly cared. The trip back to the ship usually featured rematches but they were generally lacking in enthusiasm. Most simply stood around wondering if the next island or possibly the one after that might be different. It never was. One time when I went with the representative from our Division to draw our two cases of beer for liberty the representative from the I Division (the radar girls) failed to show. Micks had noted that I was wearing a shirt belonging to someone in the I Division (laundry snafu) so we proceeded to draw their beer also. A fine time was had by all (except, possibly, for the I Division).

Life at sea was fantastic. Just like I would imagine a cruise would be except for the food, the watches, the work and the uncertainty. The longest I was at sea at a stretch was, I think, sixty some days, off Okinawa. Although life in an anchorage featured movies, boxing matches, reduced watches and an infrequent opportunity to visit another ship. I much preferred life at sea. I can’t think of anything I’ve ever done that was as restful as lying on a ready-box in the forecastle (focs’l) looking down at the waves, the occasional flying fish or the more infrequent porpoises. Doesn’t sound like much but as they would probably say in the beer commercials “it probably just doesn’t get any better than this”.

War at sea was pretty much long stretches of unimaginable boredom made worse by the veterans of Savo Island and Santa Cruz (earlier battles during which the mighty South Dakota ended up with some good press) reliving their earlier glory. Scuttlebutt (civilian counterpart-grapevine) would have us going to Murmansk or some other fictional place (“Honest, I saw them loading anti-freeze”). Although I heard all of the stories about drinking after shave lotion, torpedo juice and raisin jack my shipboard drinking was limited to a little smuggled Jack Daniels and some pink lady souped up with a little optical alcohol. Tokyo Rose was popular and frequently told us where we were headed (“What in the Hell is an Iwo Jima”) and we once had the honor of being sunk on her show.

We had a 78 rpm record player in the plotting room and on one of our visits to Pearl we sent money with one of the officers (Lt. Dart, I think) to buy us some new records. Whoever it was came back with the original cast album from “Oklahoma”. I’ve no doubt that “Oklahoma” was a fine play and that even the music was passable if you only had to hear it once. About the thirty eight hundredth time I heard “Pore Jud Is Daid” I wanted nothing more than to throw up. One by one the records went crashing down in a thousand fragments followed by “I tole you if I hear that goddam record once more I’m gonna hammer your ——- — clear back to the swamps of Georgia where you and it both come from.” The South Dakota was pretty much crewed by rednecks from Georgia, Alabama and the Carolinas, many of whom had been in the peacetime Navy and were not particularly noted for their diplomacy.

We took a bomb off Saipan and were headed for Pearl for repairs. Our executive Officer at the time was Cmdr. Harold Stassen (onetime Governor of Minnesota and, since then, perennial presidential aspirant) who flew ahead to make the necessary arrangements. Being a politician Mr. Stassen proceeded to have our orders changed from Pearl to Bremerton, Washington. Not only that, he arranged for railroad ticket sellers to join us in Pearl so that we could buy our tickets on the way. When we hit Seattle a ferry boat tied up alongside while we were still underway. We went over the side on Jacobs ladders and were on our way to the depot before the ship ever reached her berth. Twenty glorious days later I was back aboard. Bill Givens had been about the only guy around Boone but we had a good time.

I was overseas for about twenty months and pretty much made the rounds (Marshall Islands, Gilberts, Admiralties, Truk, Ponape, Philippines, Marianas, Okinawa, the China Sea etc.) We bombarded shore installations on Saipan, Okinawa and, of course, the Japanese mainland. We went through Typhoons where the wind velocity measuring devices blew away. We were in the vicinity when the Destroyers Hull, Spence and Monahan went down due to lack of fuel to maintain their heading into the wind. We were there when the Kamikazes hit the Randolph, the Bunker Hill (where my cousin, Bill Porter, was a gunner), the Franklin and numerous others. We saw a tanker torpedoed by a midget submarine in the Ulithi anchorage.

The kamikaze, or suicide, pilot was something new around the time of the Philippines invasion. At the time we had understood this sort of thing to be just another example of the fanaticism which seemed to be a part of the Japanese national character and which made them such a fearsome adversary. It later developed that their military was indeed scraping the bottom of the materiel barrel and that this was one of the few viable alternatives to surrender. It still takes a lot of guts to go on a search mission when you know that if you locate a target you won’t need to worry about navigating your way back to the base. It was later discovered that most of the kamikaze pilots were students rather than experienced aviators and ordinarily had just a few hours of flight time. They were not, as a result, as successful as would otherwise been the case.

Another interesting sidelight to the war with Japan – Before the war began our cryptanalysts had succeeded in breaking the most secret of the Japanese military codes. We were amazingly successful in keeping the fact that we had broken their code a secret. This permitted our submarines to go on patrol knowing where and when targets were to be found. To me the most amazing use of intercepted data occurred when a squadron of P38s intercepted the Japanese plane carrying Admiral Yamamoto (the Japanese top admiral) over one of the islands when he was on an inspection trip. Even this didn’t tip the Japanese to the fact that their secrets were not secrets any more. Like the Japanese, I knew nothing about any of this until sometime after the war had ended. I thought that our victories, such as Midway, were simply the result of superior naval strategy by people like King, Nimitz, Halsey and Spruance.

One night when I got off watch and went to my bunk we had been surrounded by our normal complement of ships; a couple of carriers, another battleship, a few cruisers and a dozen or so Destroyers. When I got up for dawn alert we were surrounded by the greatest naval armada ever assembled. This was in preparation for the invasion of Saipan. To look from horizon to horizon and see nothing but ships where yesterday there had been nothing but empty sea was probably the most impressive sight I’ve ever seen. What had the potential of being the most exciting night of the Pacific war (at least from my standpoint) occurred during the invasion of the Philippines. The Seventh fleet (old battleships, destroyer escorts and escort carriers) were protecting the invasion site while we (the Third fleet) were cruising around trying to stir up a battle with the Japanese navy. A large force including carriers was reported to the north, off Luzon. We went after them at a rollicking 28 knots (the only time the old girl ever got near design speed). The speed was too much and our fleet diminished rapidly until I began to hope that we wouldn’t find their ships. The northern force turned out to be a decoy and the main body of the Japanese battle fleet had been sneaking through the islands to get at our invasion fleet in spite of being harassed by torpedo boats and a destroyer torpedo attack. Our escort carriers (converted merchant ships) came under fire from the main Japanese battle fleet. Bull Halsey had been badly snookered by the Japanese and, had the enemy not chickened out because of uncertainty as to the location of our carriers, this could well have been the greatest debacle of the Pacific war. Our press was not too good after that.

When the war ended we had been bombarding Hamamatsu and Kamaishi as well as escorting carriers whose planes had been ripping up the islands. We saw, at times, the endless streams of B-29s on their way to their nightly pyrotechnics. From this we went to hightailing it directly away from Japan at flank speed. Until we heard the story of the atomic bomb we had been unsure of what type weapon the Japanese might have come up with to force us to cut-and-run like we did. We were there, in Tokyo Bay, when the surrender documents were signed aboard the U. S. S. Missouri.

(From John – The surrender was signed aboard the USS Missouri, a newer battleship but one with a far less illustrious record than the South Dakota. The selection of the Missouri rather than the South Dakota or one of the other more distinguished ships present was not without controversy. Dick recently read that the South Dakota may have been the original choice but perhaps Truman’s ties to Missouri or other politics came into play. Regardless, Dick was glad the signing did not occur on his ship because it would undoubtedly have meant many hours of ship cleaning duty. He was able to watch the signing through binoculars from the comfort of the battleship South Dakota.)

Having expected to have to go through an invasion of the home islands I doubt that anyone (other than possibly those in the know about the bomb) expected the war to end in less than two years. We headed for San Francisco shortly thereafter and received a royal welcome upon arrival. We later went through the Panama Canal on our way to Philadelphia where the old girl went into mothballs. A big chapter in my life had ended.

This war saw horror on a scale far larger than ever previously imagined. It saw the holocaust, the Bataan death march, the indiscriminate bombing of civilians in England and Germany, the terrible fire-bombing of the Japanese homeland and the use of the ultimate horror, the Atomic bomb. The argument still goes on as to whether the Japanese were ready to surrender regardless of the atomic bomb. I choose to think that the war would, indeed, have gone on until there was nothing left to defend had we not bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In retrospect I must say that I had a very good war. I saw a lot of the world. I had pretty good facilities and adequate food. I met a lot of pretty good people. Although I didn’t leave any lasting marks I felt that I was a part of history.

-RHP